The Mosque as a Community in Denmark

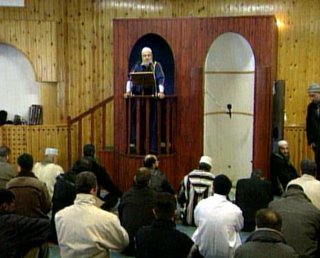

(Abu Laban in the mosque in outer Nørrebro. Even this large mosque and muslim cultural centre is in an abandoned business complex. There are no minarets or other outward signs of it being a mosque)

(Abu Laban in the mosque in outer Nørrebro. Even this large mosque and muslim cultural centre is in an abandoned business complex. There are no minarets or other outward signs of it being a mosque)The Danish sociologist of religion Lene Kühle of Aarhus University has made research on Danish mosques. The research results are published in the book "Mosques in Denmark - islam and Muslim prayer sites", Univers Publishers.

There are about 200.000 muslims in Denmark. She has found 114 "mosques", or prayer "places" ("Mosque" is too ambitious a term) , where the Danish muslims practise their religion. These "mosques" are very unobtrusive, you might even say subdued. It is as if the muslims are aware of the fact that they're perhaps not so welcome in the otherwise very homogeneous Danish society. Anyway, the mosques are not as visible as the churches which tower over hamlets and towns from ancient times.

If you expected the mosques to be hotbeds of religious fervour and revolutionary (terrorist) activity, you'll be disappointed, Kühle's research shows. In most places she found a group of men playing cards and women chatting. The most noisy activity may be a game of table football. It is only in a small group of mosques, about 37 in all, that Kühle calls "organization mosques" that you find a religious head of some standing and with some religious education, an Imam, who may be sent from the "mother organization" in the home country, for instance Turkey. Even these mosques are very modest with serious religious activity only during prayer. Then there are 7 larger mosques which put some emphasis on the religious message and denomination. In these places there is a recognized Imam of some standing (for instance Abu Laban) that people will travel some distance to listen to in Friday prayer. It is only these places in Copenhagen and Aarhus that have been scrutinised by Danish media and considered possible breeding grounds for anti-Western activities or propaganda. Kühle has not tried to distinguish between potentially "subversive" imams and more docile ones, as this has not been the purpose of her research, but she considers it doubtful that one can make any kind of distinction between "evil" and "good" islam. It is not possible to "paint" islam in images of "black" or "white". The mosques do not have the influence on people's minds that the media seems to have presumed, she concludes. By means of this focus we ourselves are responsible for turning religion into politics, she thinks.

We tend to equate deeply religious with fundamentalist, she says, thus seeing a menace to the cohesion of modern society and its democratic institutions. In that way we tend to see deeply religious people as threats in themselves, which is a very questionable practice. The Danish mainstream politician Villy Søvndal, who is chairman of the Socialist People's Party, is a vocal critic of the Danish participation in the Iraq war. In many other issues he has quite moderate points of view. Had he been a muslim, he would have been considered an extremist, Kühle says. We have developed a climate of debate in which we turn people, with whom we disagree, into extremists (Kühle in interview with Danish paper the Politiken May 23rd).

After the cartoons issue there has been a lot of debate on whether there is full equality between the religious communities in Denmark. The muslims' humble prayer sites might lead to the conclusion that this is not the case.

Church and state are kept separate in Denmark. About 85 per cent of the Danes are members of the Lutheran state church, and they pay a special church tax, about 1 per cent of tax declared income. The income from the church tax goes to the Lutheran church.The other recognized religious communities (included muslims) do not get any of this money, but they can finance their activities through a right to deduct the money their members pay to their religion from the declared tax income. Most of the Danish muslims are immigrants and descendants of immigrants from Turkey, the Middle East and other muslim areas. A lot of efforts are done to integrate them in the Danish society in such a way that their distinctive culture and religion is respected. Still the Danes could do a lot more.

Especially in the religious area more can be done for integration.The Danish state church should not be a church for only Christian Lutheran protestants. Perhaps it should not be called a “church”. It should either be a comprehensive umbrella for all officially recognised religions, including islam, or else the Christian church should be cut loose from the state, so all religious communities will be truly equal. Births and deaths are registered by the state church. It has been difficult for muslims in thinly populated areas to find burial places. Some have chosen to be buried in their original home lands.Omar Marzauk, a Danish comedian of immigrant background, has said jokingly that he should have been born a poodle, not a Muslim: “Dogs in this nation have their own burial grounds, and Muslims don't," he has said in one of his shows. "So I either have to be sent out of this country in a box or change my name to “Fluffy”". Like most satire, there is some truth also in this satire: Denmark's Muslims have found it hard to find land for Islamic cemeteries.Denmark is a secular country. Science and rational thought dominate. So does the official Folkekirke. The Danes, however, are not very diligent churchgoers. Many churches are practically empty during sermons on Sundays. It is only on Christmas Eve that a few Danes find it worthwhile going to church. It is not sinful not going to church. So why bother?

3 Comments:

I actually think that the only reason the 85% of danes are members of the church is because most just hasn't bothered to cancel their membership, I know that, that is the only reason I am still a member.

and why are deeply religious people not the same as fundemantalists

?

Good question. Maybe they are, but Kühle doesn't seem to think so. It is probably because fundamentalism is generally associated with something negative. Being religious is not. Being a fundamentalist is like being dogmatic, which generally is regarded as negative.

Cosmic,

This is a very good post. Mosques are like community centers. My european husband who is an atheist, second generation, was very pleased to enter mosques last summer in the ME. It was the firat time for him and he found people taking a nap inside to flee the outside heat. women sitting in a circel chatting while patting their children. he thougt that that was a much less restrictive religion than christianity where a prayer place is not that open to earthly human activities.

And mosques are not a place for political and religious fervour (it is not like a church). I think political and religious fanatism arise when the community feels threatened. A threat to the community impairs indiviudals abilities to live their religion as individuals and hardens the communautarist aspect of religion.

Post a Comment

<< Home